Unexpected findings: prehistoric megalodon shark differed from great white shark in body shape and lifestyle

22. January 2024

Palaeontological research team furnishes new and better insights into the biology

of one of the largest marine carnivores ever to have existed.

Scientists from the University of Vienna and the Natural History Museum Vienna are members of an international research team that is currently making waves in the expert community: the team was able to demonstrate that – contrary to previous assumptions – the iconic megalodon shark (Otodus megalodon) was markedly more slender than a white shark and also had a different lifestyle. The researchers' findings have now been published in the Palaeontologia Electronica journal.

Scientists from the University of Vienna and the Natural History Museum Vienna are members of an international research team that is currently making waves in the expert community: the team was able to demonstrate that – contrary to previous assumptions – the iconic megalodon shark (Otodus megalodon) was markedly more slender than a white shark and also had a different lifestyle. The researchers' findings have now been published in the Palaeontologia Electronica journal.

Megalodon,

the gigantic prehistoric shark that first appeared about 15 million years ago and became extinct 3.6 million years ago, is

an icon of the prehistoric era. Famous for its giant teeth, it was one of the largest marine carnivores ever to live. Given

its considerable impact on marine ecosystems, it is still a popular research subject today. In order to better understand

its biology and, thus, its behaviour, the correct reconstruction of its body shape is of vital importance. Previously, this

constituted a challenge for researchers, since only teeth and vertebrae have been preserved, but no complete skeleton.

Previous assumptions

The fact that, like the white shark, megalodon was able to partially regulate its body temperature (“regional warm-bloodedness”) and had similarly shaped teeth, was long considered to mean that its body shape also resembled that of the modern-day white shark. Accordingly, the white shark was traditionally used as a model species for interpreting the lifestyle and shape of megalodon – an approach that has now been thrown into doubt by the latest research findings, as palaeobiologist Jürgen Kriwet from the Department of Palaeontology at the University of Vienna explains: “In the past, the shape assumed for megalodon led researchers to believe that it was a fast swimmer and resembled today’s mackerel sharks – the so-called lamnid sharks –, a family that also includes the white shark. There are, however, some weak points in this scientific reasoning.”

How the story continues

Based on a partially preserved vertebral column of megalodon and some modern-day lamnid specimens, the research team has now reassessed the 2D and 3D reconstruction of the prehistoric shark’s body shape. It turned out that the assumptions of previous studies were incorrect in large parts. “Using an incomplete vertebral column without additional skeletal elements such as the skull and comparing it with a CT scan of a young white shark without taking into account ontogenetic changes in order to reconstruct the megalodon’s body shape and, thus, biological aspects, is a greatly error-prone approach,” notes palaeobiologist Jürgen Kriwet. But despite their deficits, previous studies have still furnished one important pointer for megalodon’s body shape: it was elongated relative to the body of the modern white shark.

Reassessing body shape and lifestyle

The anatomical comparison of the vertebral columns of modern-day mackerel sharks with that of megalodon shows that the ancient giant shark was longer and slimmer. Even if its actual body shape has not been completely ascertained, the new findings are of great biological significance. “In combination, this gives us the picture of a relatively slender and elongated, regionally warm-blooded, rather slow-swimming top predator, that occupied a similar or even higher trophic position than today’s great white shark,” says palaeobiologist Patrick L. Jambura from the Department of Palaeontology at the University of Vienna. “Our study shows that a thorough analysis of all available data and a careful selection of modern-day sharks as model organisms can provide important pointers to the lifestyle and biology of extinct shark species,” adds palaeobiologist Julia Türtscher from the Department of Palaeontology at the University of Vienna.

Although it reigned supreme at the top of the food chain for almost 12 million years, megalodon became extinct roughly 3.6 million years ago. Its downfall may have been brought about by climatic changes, but also by today’s great white sharks – which probably reach sexual maturity more quickly. “Understanding the success, but also the extinction, of such marine predators is of great significance since it enables us to draw conclusions about the future of today’s top predators, which are indispensable for the ecological balance of the oceans,” explains palaeontologist Iris Feichtinger from the Natural History Museum Vienna.

Publication in Palaentologia Electronica: White shark comparison reveals a slender body for the extinct megatooth shark, Otodus megalodon (Lamniformes: Otodontidae)

Phillip C. Sternes, Patrick L. Jambura, Julia Tu?rtscher, Ju?rgen Kriwet, Mikael Siversson, Iris Feichtinger, Gavin J. P. Naylor, Adam P. Summers, John G. Maisey, Taketeru Tomita, Joshua K. Moyer, Timothy E. Higham, Joa?o Paulo C. B. da Silva, Hugo Bornatowski, Douglas J. Long, Victor J. Perez, Alberto Collareta, Charlie Underwood, David J. Ward, Romain Vullo, Gerardo Gonza?lez-Barba, Harry M. Maisch IV, Michael L. Griffiths, Martin A. Becker, Jake J. Wood, Kenshu Shimada;

https://palaeo-electronica.org/content/2024/5079-megalodon-body-form

Please find press material for download under the following link:

https://www.nhm-wien.ac.at/en/press_releases2024/megalodon

Scientific enquiries:

Iris Feichtinger

Geology and Paleontology department, NHM Vienna

https://www.nhm-wien.ac.at/iris_feichtinger

iris.feichtinger@nhm-wien.ac.at

Tel.: +43 (1) 52177-596

Prof. Dr. Jürgen Kriwet

Institute of Paleontology, University Vienna

1090 – Wien, Josef-Holaubek-Platz 2 (UZA II)

Tel.: +43 (1) 4277-53520

Mobil: +43 664 817 57 76

juergen.kriwet@univie.ac.at

Previous assumptions

The fact that, like the white shark, megalodon was able to partially regulate its body temperature (“regional warm-bloodedness”) and had similarly shaped teeth, was long considered to mean that its body shape also resembled that of the modern-day white shark. Accordingly, the white shark was traditionally used as a model species for interpreting the lifestyle and shape of megalodon – an approach that has now been thrown into doubt by the latest research findings, as palaeobiologist Jürgen Kriwet from the Department of Palaeontology at the University of Vienna explains: “In the past, the shape assumed for megalodon led researchers to believe that it was a fast swimmer and resembled today’s mackerel sharks – the so-called lamnid sharks –, a family that also includes the white shark. There are, however, some weak points in this scientific reasoning.”

How the story continues

Based on a partially preserved vertebral column of megalodon and some modern-day lamnid specimens, the research team has now reassessed the 2D and 3D reconstruction of the prehistoric shark’s body shape. It turned out that the assumptions of previous studies were incorrect in large parts. “Using an incomplete vertebral column without additional skeletal elements such as the skull and comparing it with a CT scan of a young white shark without taking into account ontogenetic changes in order to reconstruct the megalodon’s body shape and, thus, biological aspects, is a greatly error-prone approach,” notes palaeobiologist Jürgen Kriwet. But despite their deficits, previous studies have still furnished one important pointer for megalodon’s body shape: it was elongated relative to the body of the modern white shark.

Reassessing body shape and lifestyle

The anatomical comparison of the vertebral columns of modern-day mackerel sharks with that of megalodon shows that the ancient giant shark was longer and slimmer. Even if its actual body shape has not been completely ascertained, the new findings are of great biological significance. “In combination, this gives us the picture of a relatively slender and elongated, regionally warm-blooded, rather slow-swimming top predator, that occupied a similar or even higher trophic position than today’s great white shark,” says palaeobiologist Patrick L. Jambura from the Department of Palaeontology at the University of Vienna. “Our study shows that a thorough analysis of all available data and a careful selection of modern-day sharks as model organisms can provide important pointers to the lifestyle and biology of extinct shark species,” adds palaeobiologist Julia Türtscher from the Department of Palaeontology at the University of Vienna.

Although it reigned supreme at the top of the food chain for almost 12 million years, megalodon became extinct roughly 3.6 million years ago. Its downfall may have been brought about by climatic changes, but also by today’s great white sharks – which probably reach sexual maturity more quickly. “Understanding the success, but also the extinction, of such marine predators is of great significance since it enables us to draw conclusions about the future of today’s top predators, which are indispensable for the ecological balance of the oceans,” explains palaeontologist Iris Feichtinger from the Natural History Museum Vienna.

Publication in Palaentologia Electronica: White shark comparison reveals a slender body for the extinct megatooth shark, Otodus megalodon (Lamniformes: Otodontidae)

Phillip C. Sternes, Patrick L. Jambura, Julia Tu?rtscher, Ju?rgen Kriwet, Mikael Siversson, Iris Feichtinger, Gavin J. P. Naylor, Adam P. Summers, John G. Maisey, Taketeru Tomita, Joshua K. Moyer, Timothy E. Higham, Joa?o Paulo C. B. da Silva, Hugo Bornatowski, Douglas J. Long, Victor J. Perez, Alberto Collareta, Charlie Underwood, David J. Ward, Romain Vullo, Gerardo Gonza?lez-Barba, Harry M. Maisch IV, Michael L. Griffiths, Martin A. Becker, Jake J. Wood, Kenshu Shimada;

https://palaeo-electronica.org/content/2024/5079-megalodon-body-form

Please find press material for download under the following link:

https://www.nhm-wien.ac.at/en/press_releases2024/megalodon

Scientific enquiries:

Iris Feichtinger

Geology and Paleontology department, NHM Vienna

https://www.nhm-wien.ac.at/iris_feichtinger

iris.feichtinger@nhm-wien.ac.at

Tel.: +43 (1) 52177-596

Prof. Dr. Jürgen Kriwet

Institute of Paleontology, University Vienna

1090 – Wien, Josef-Holaubek-Platz 2 (UZA II)

Tel.: +43 (1) 4277-53520

Mobil: +43 664 817 57 76

juergen.kriwet@univie.ac.at

Größenvergleich von Zähnen eines heutigen ca. 2,7m langen Weißen Hais Carcharodon carcharias (A) und eines ca. 9m langen Otodus

megalodon aus dem Miozän von South Carolina, U.S.A. (B).

© J. Kriwet

© J. Kriwet

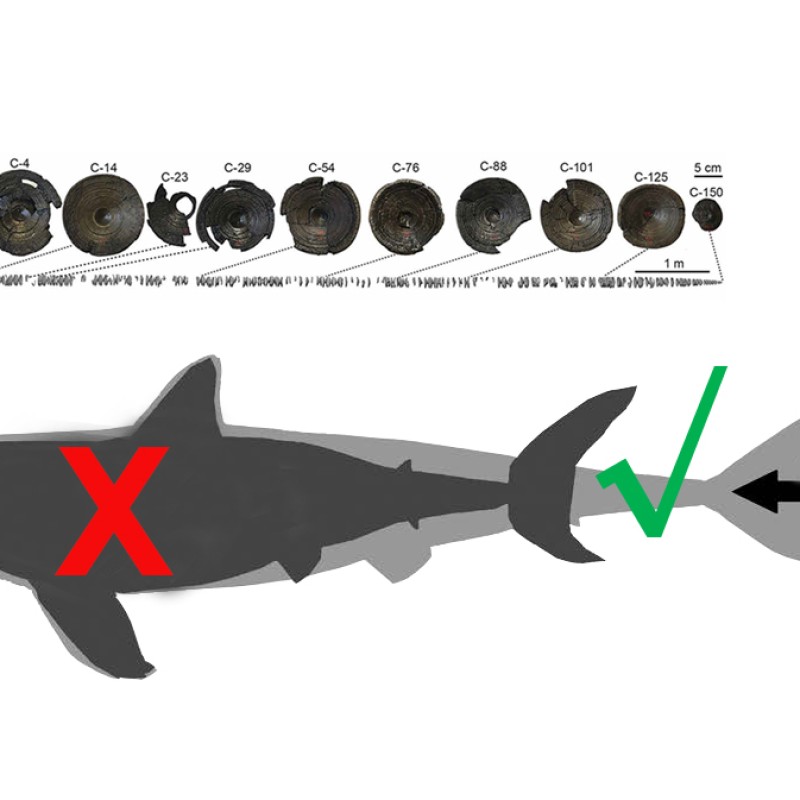

A: Unvollständige, Otodus megalodon zugeschriebene Wirbelsäule mit 141 erhaltenden Wirbelkörpern im Königlich Belgisches Institut

für Naturwissenschaften. ©Cooper et al., Sci. Adv. 8, eabm9424, 2022.

B: Bisherige rekonstruierte Körperform von Otodus megalodon (dunkelgraue Silhouette), die weitgehend mit der des modernen Weiße Haies übereinstimmt, überlagert von der neu interpretierten Körperform (hellgraue Silhouette). Die genaue Körperlänge, die Form des Kopfes sowie die Positionen und Umriss der Flossen bleiben weiterhin spekulativ, da nur Zähne, Wirbelkörper und Hautschuppen bekannt sind. © Verändert nach Sternes et al.

B: Bisherige rekonstruierte Körperform von Otodus megalodon (dunkelgraue Silhouette), die weitgehend mit der des modernen Weiße Haies übereinstimmt, überlagert von der neu interpretierten Körperform (hellgraue Silhouette). Die genaue Körperlänge, die Form des Kopfes sowie die Positionen und Umriss der Flossen bleiben weiterhin spekulativ, da nur Zähne, Wirbelkörper und Hautschuppen bekannt sind. © Verändert nach Sternes et al.