Hall 6 - The Earth – a dynamic Planet

In hall 6 - the geology hall - the relationship between the lithospere (the Earth's crust and the upper part of the mantle) and the biosphere

(which includes all living things on earth) is highlighted.

The exhibition spans from the structure of the earth to the Anthropocene - the age in which humans began to emerge as a geological

force. Interactive stations allow visitors to experience changes in the earth up to the present day and show how life became

possible.

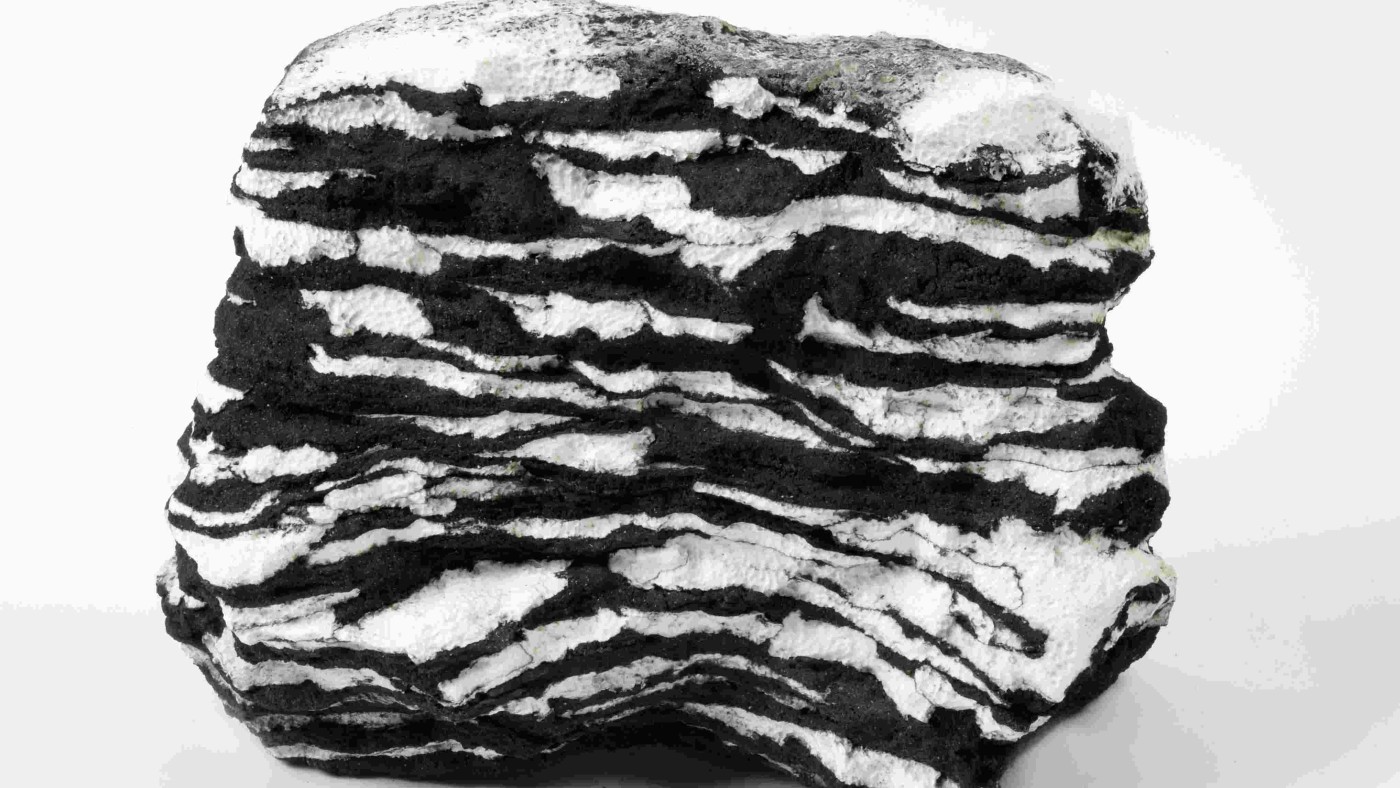

The exhibition also shows the danger posed by methane ice as a climate killer, using examples from the geological past. The melting of methane ice 55 million years ago was followed by a climatic catastrophe with high temperatures and great drought, which led to the dwarfing of the animal kingdom. A similar event 8,000 years ago triggered a tsunami, whose 20-meter-high tidal wave devastated the coasts of northern Europe. In terms of warming oceans, melting methane ice deposits are a very real threat to us and our already battered

climate system.

Another unusual theme of the exhibition is the rhythms that shape our planet. Life on Earth is determined by the movements between the Sun, Earth, and Moon. Cycles such as day and night, the phases of the moon and the seasons determine the course of life and are directly perceptible to plants, animals, and humans. In an audiovisual installation, the exhibition makes it possible to experience these rhythms as “world music” in an unusual way.

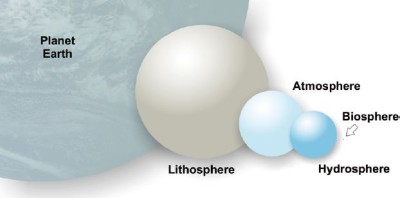

The spheres of planet Earth

- The lithosphere is the size of a ball with a diameter of 4,000 km.

- The atmosphere is the size of a ball with a diameter of 2,000 km.

- All the water on Earth would fit into a ball with a diameter of 1,400 km.

- The entire biosphere is the size of a ball with a diameter of just 15 km.

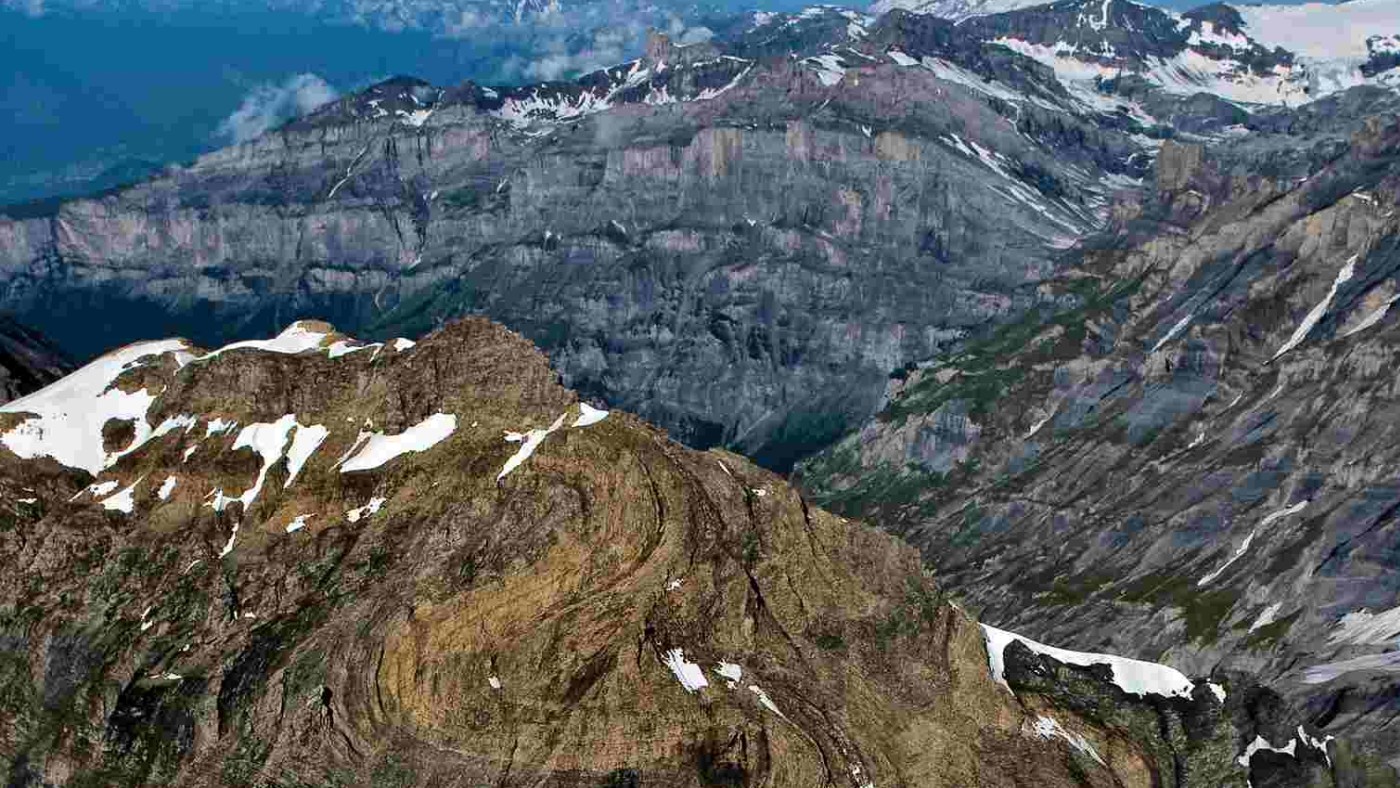

Fragile as stone

The structure of the Earth

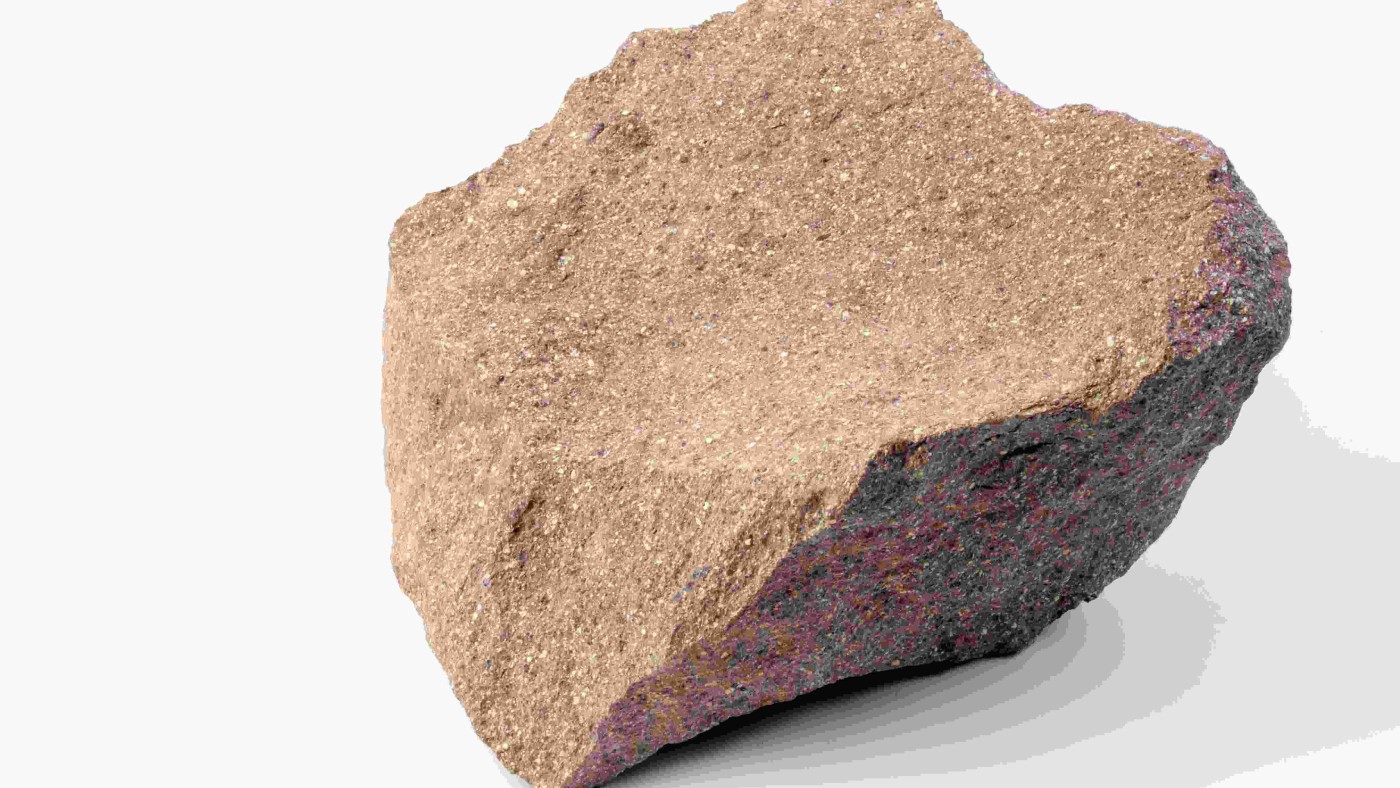

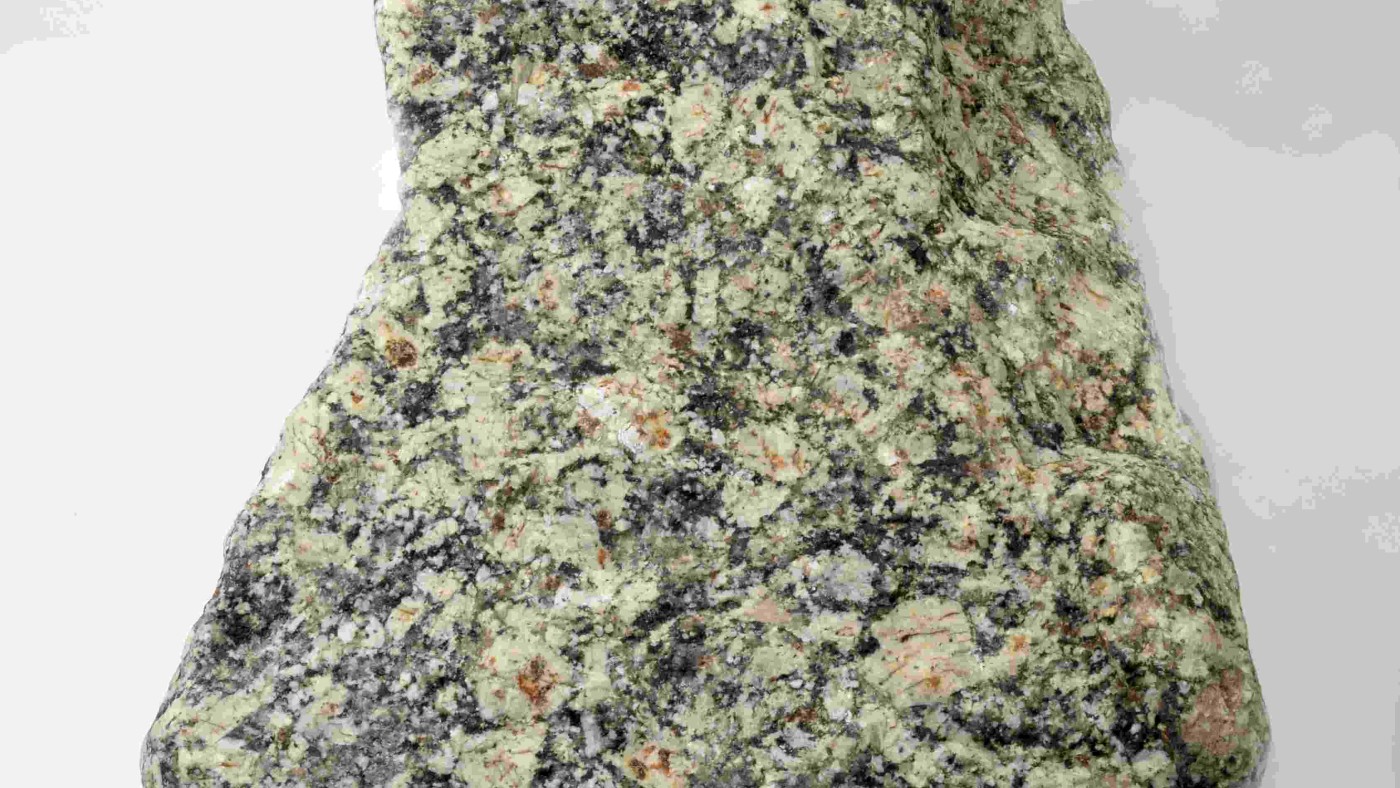

Oceanic and continental crust form the uppermost parts of the Earth’s surface. The oceanic crust, which is about 5 to 10 kilometers thick, consists mainly of magmatic rocks, such as gabbro and volcanic basalt. The continental crust, which is 30 to 60 kilometers thick, is mainly made up of rocks with a high quartz content, such as granite and the volcanic rock rhyolite.

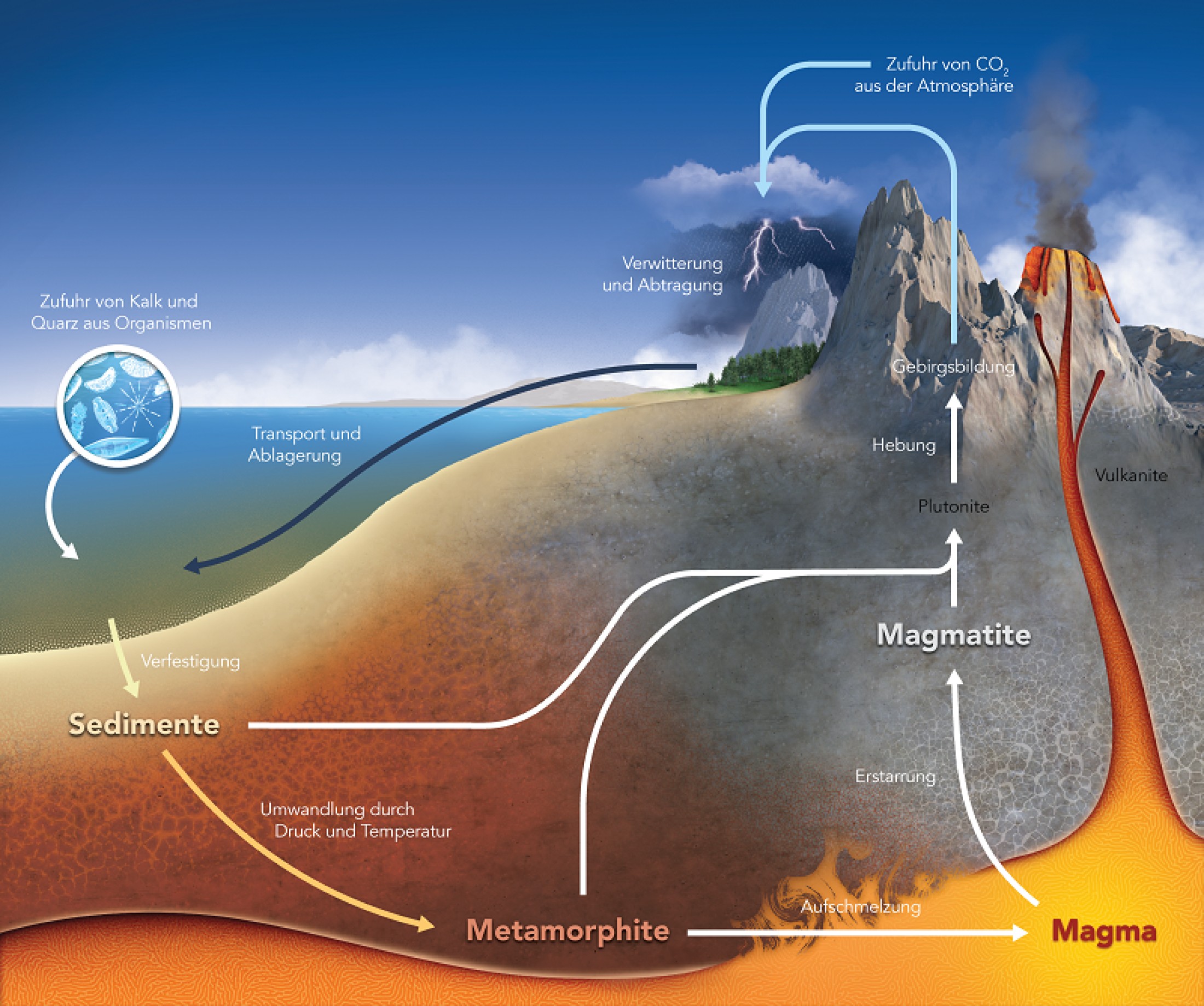

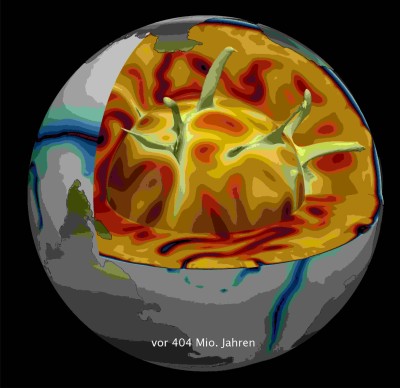

The Earth’s mantle is solid but malleable. It extends from the Earth’s crust to the Earth’s core at a depth of 2,900 km. Temperatures inside the mantle can reach up to 3,500 °C as you approach the Earth’s core. Typical mantle rocks are peridotite and eclogite. The Earth’s mantle is in constant motion. Hot material from near the Earth’s core slowly moves upwards, while cooler and denser rock from the upper region sinks downwards. This slow circular process takes many millions of years. Close to the Earth’s crust the rock can melt because the pressure is lower. New magmatic rocks are formed or come to the surface through volcanoes.

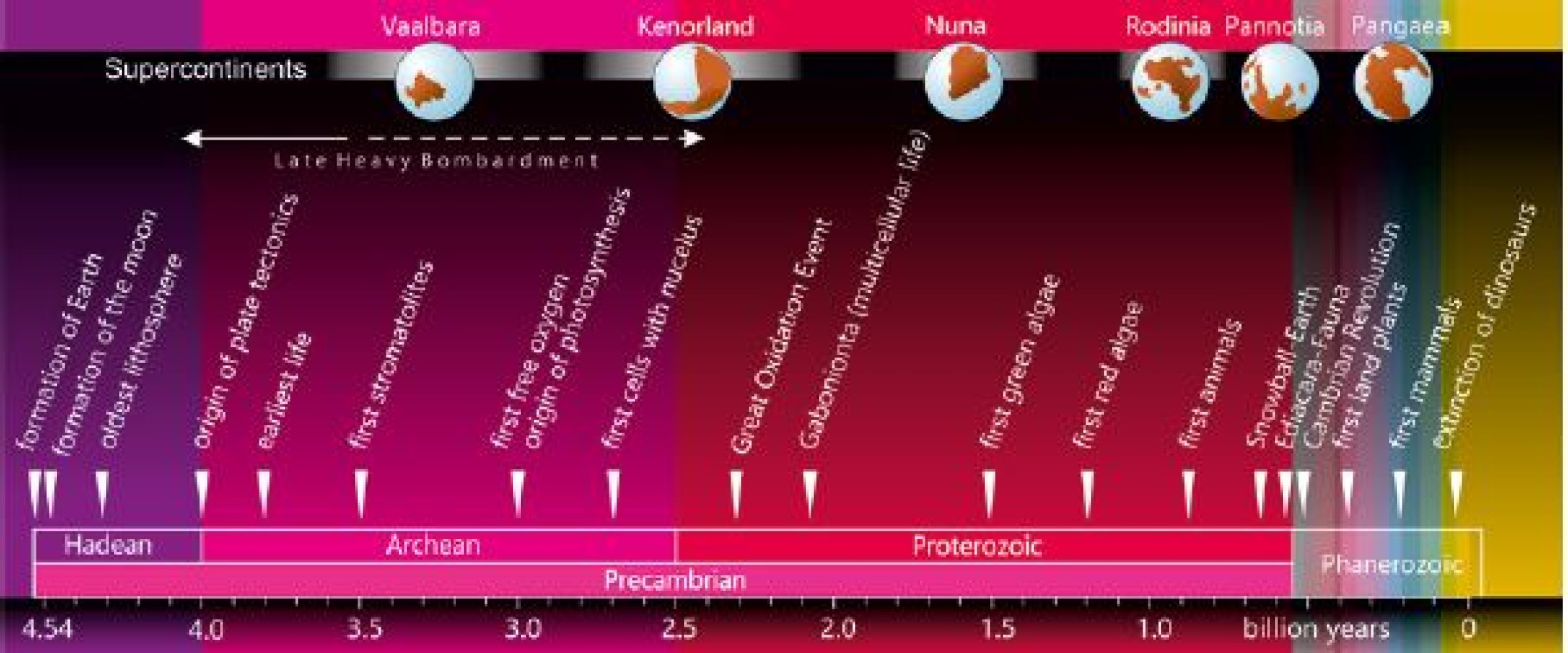

Geological revolutions of life

The colors of the Earth

Life originated about 3.8 billion years ago. One of its most important “inventions” is photosynthesis. This phenomenon, which developed around 3.4 billion years ago, enables plants and plankton to absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and release oxygen as a “waste product”. Finally, 2.4 billion years ago, so much oxygen had accumulated in the atmosphere that the Earth began to “rust”. This event is known as the Great Oxidation Event. Newly formed minerals changed the appearance of the Earth forever. Without oxygen we would have neither the brown of the soil nor the yellow of the desert.

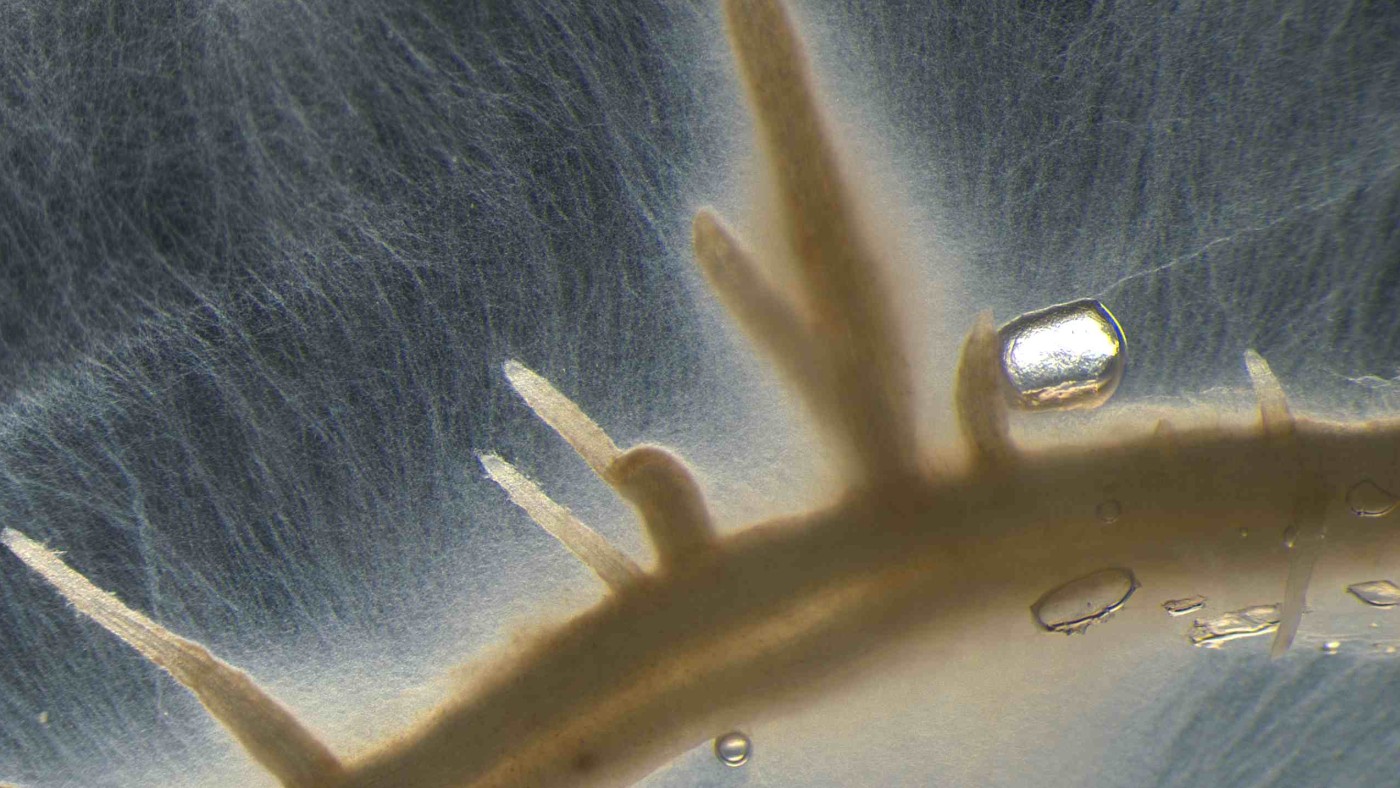

At the interface between the lithosphere and the atmosphere, life itself has created a unique habitat: the soil. Soil formation began only 470 million years ago when plants spread onto the mainland. The principle remains the same today and is based on the symbiosis between fungi and the roots of plants. The fungi dissolve nutrients from the rock and pass them on to the plants. The plants “feed” the fungi with sugar. This symbiosis led to a completely new form of weathering, resulting in enormous amounts of nutrients becoming available to life.

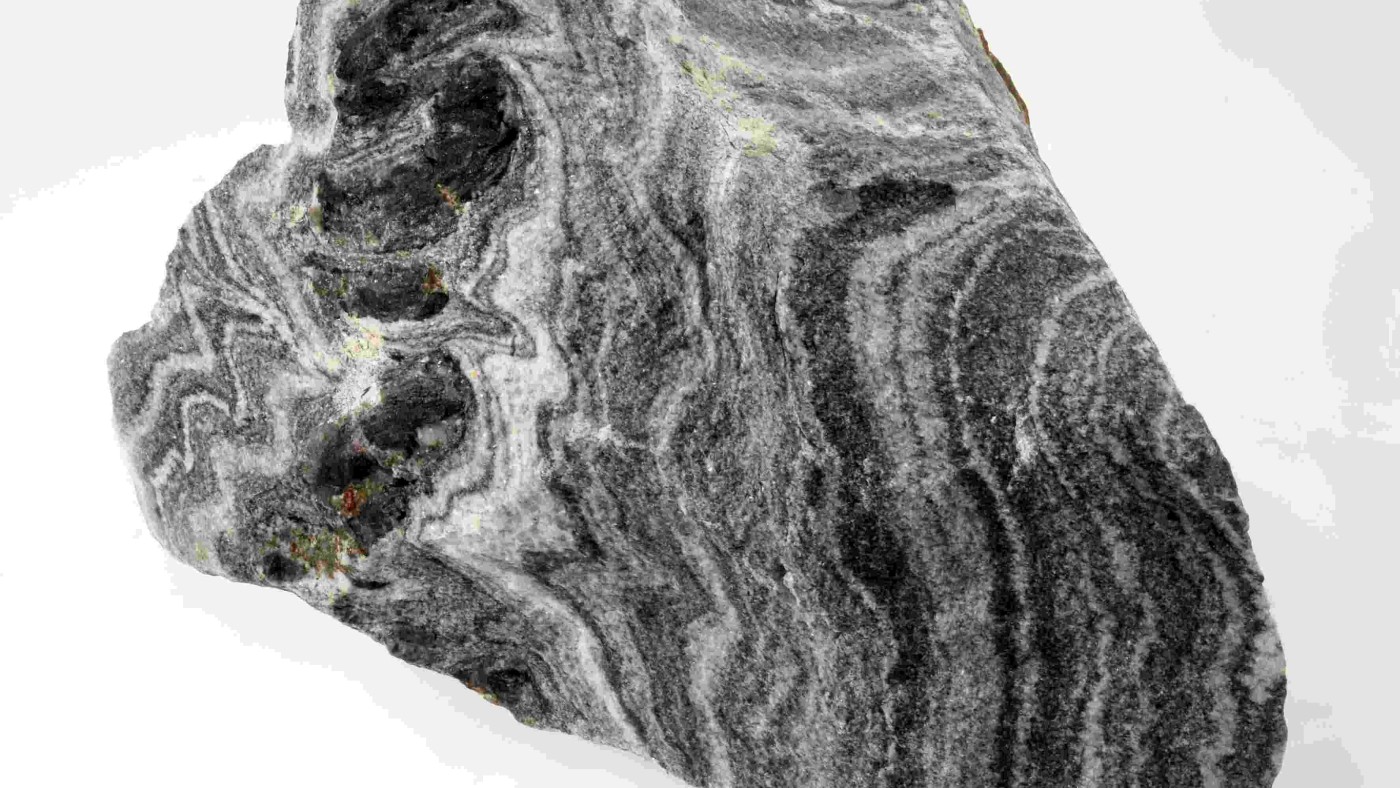

Written in stone

The formation of mountains and tectonic plate activity pulls rocks down into the Earth’s crust, where they are transformed. Depending on the pressure and temperature, their structure changes and new minerals are generated. This “fingerprint” makes it possible to calculate at which depth a rock was formed. Under pressure, granite or even sandstone can be turned into gneiss. Former coral reefs become marble, and volcanic basalt is transformed into amphibolite.

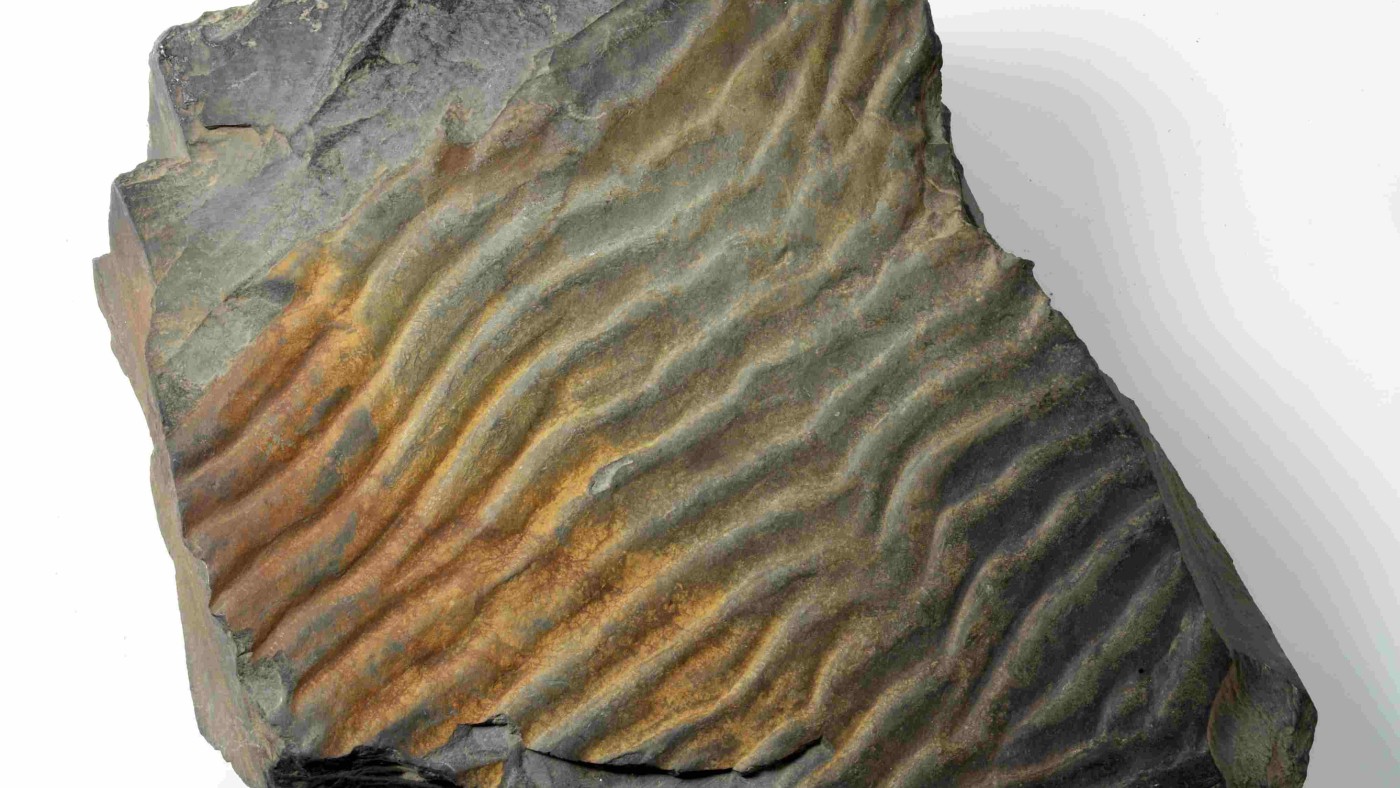

sand, and gravel – are formed by the weathering of rocks. Just a few kilometers thick, they represent merely the thin skin of the lithosphere. They can contain remains of living organisms and are therefore important carbon dioxide reservoirs. Living organisms themselves can also form sediments. There are whole mountains made up entirely of shells from unicellular organisms such as calcareous foraminifera, calcareous nannoplankton, or siliceous shells of diatoms.

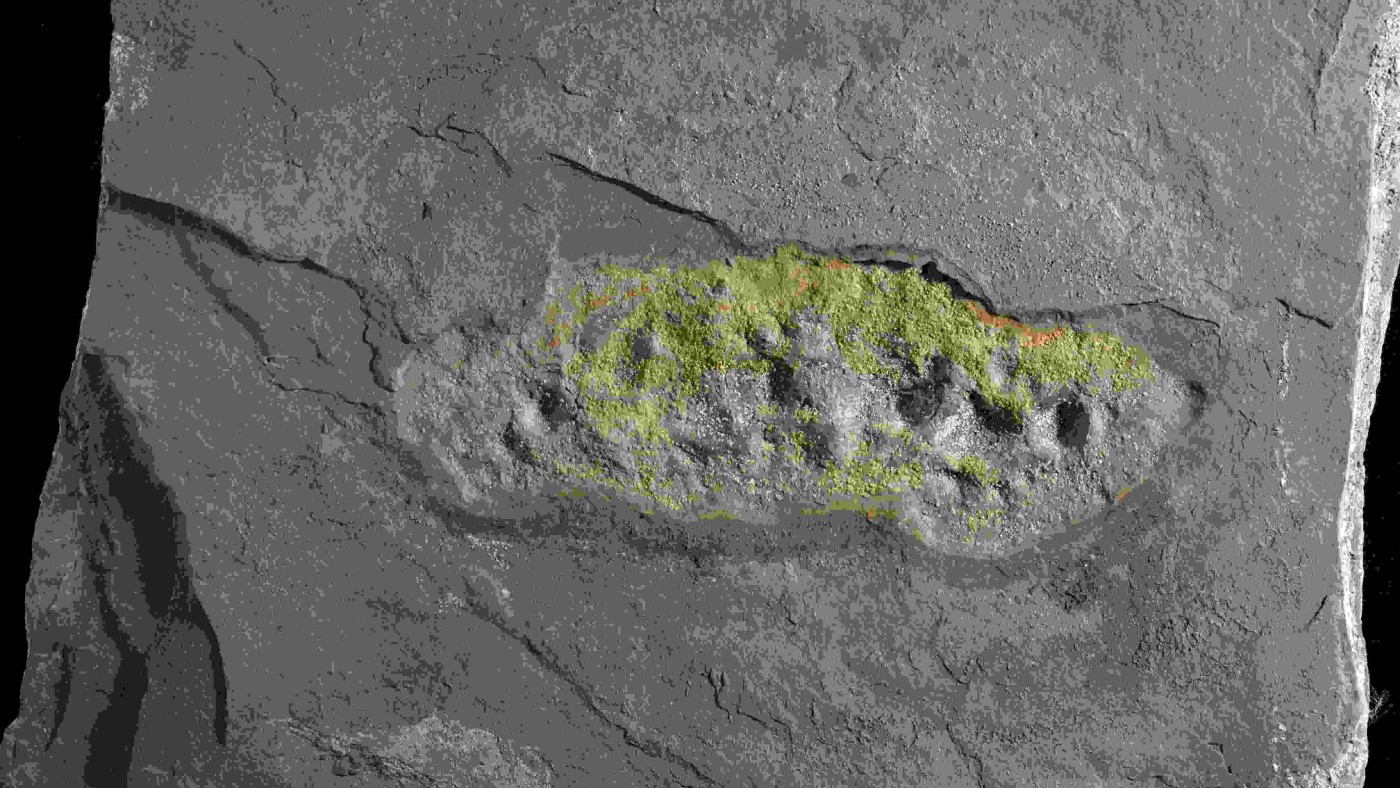

It could have turned out quite differently

different shapes suggest different ways of life. These unique fossils are currently only on display at the Natural History Museum Vienna. They were several centimeters in size but soon died out due to a sharp drop in oxygen levels in the atmosphere. Without this disaster, life would have developed in a completely different way. It was not until a billion years later that multi-celled organisms emerged once again.

The Industrial Design class at the University of Applied Arts Vienna carried out a project investigating what the world might look like if the Gabonionta had evolved. These fictional scenarios do not claim to be scientifically accurate, but are instead intended to illustrate the infinite variety of paths that were open to life ... and perhaps still remain open?

Life as a geological force

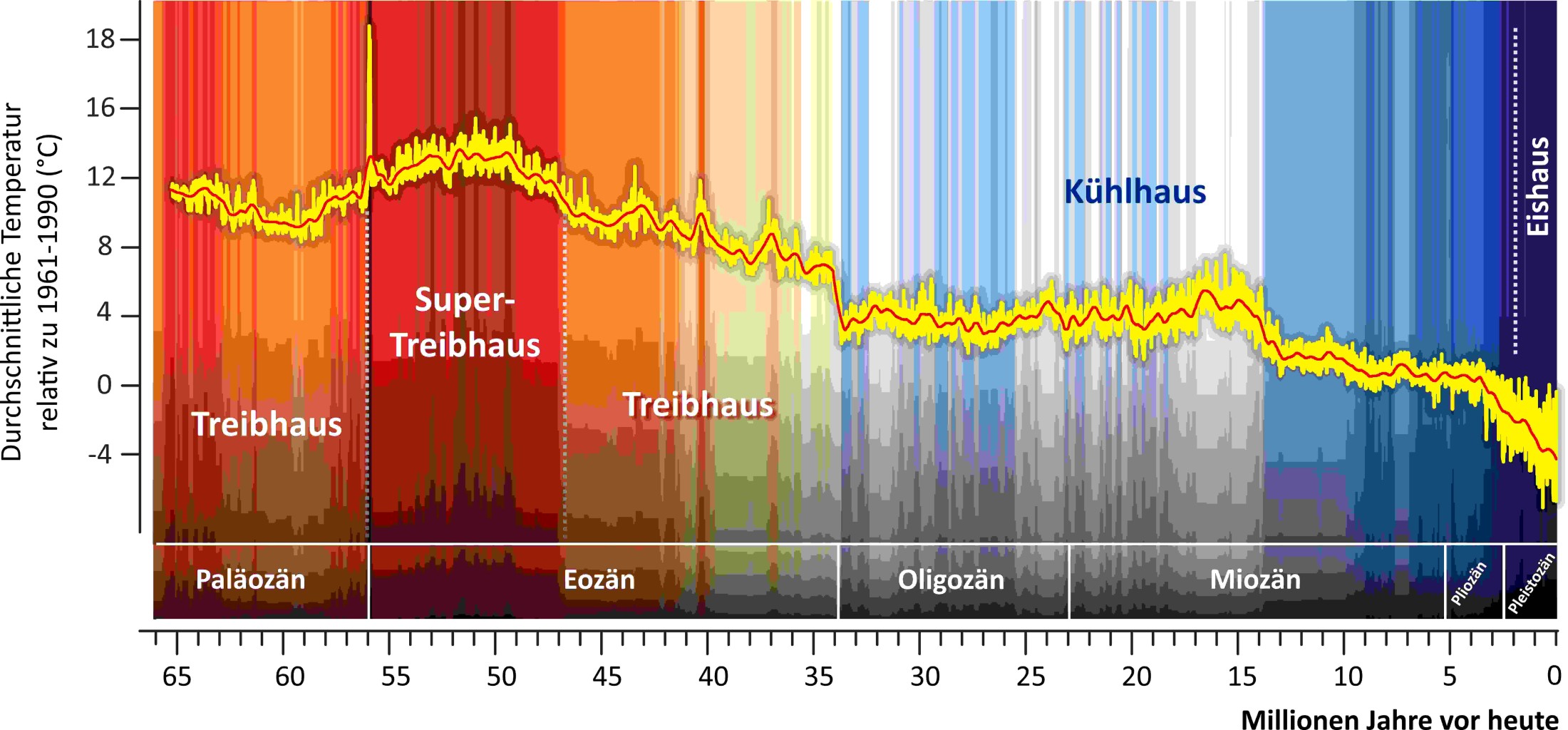

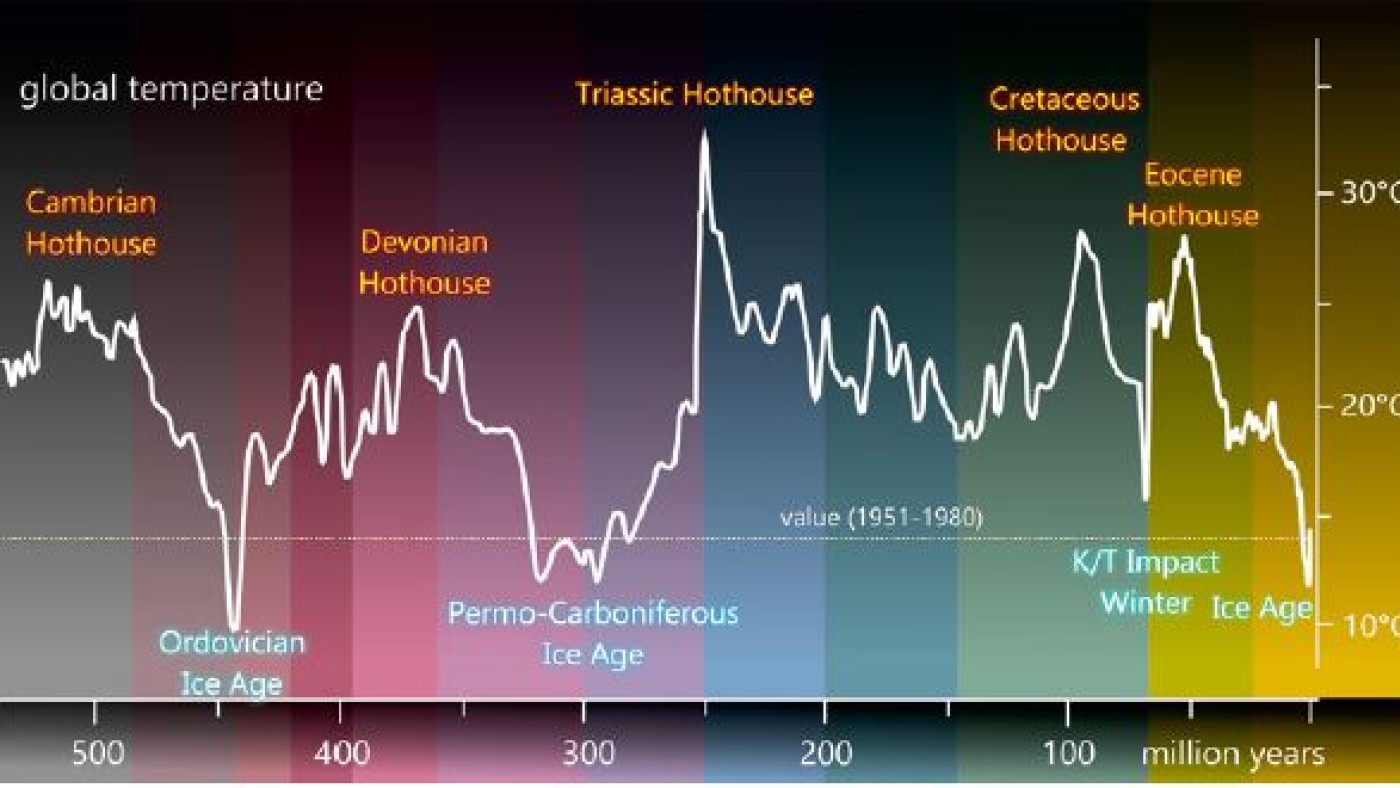

formed by microorganisms: methane ice and manganese nodules. Due to the changing CO2 concentration in the atmosphere, the temperature also was subject to large fluctuations. Particularly warm phases of Earth’s history were the Early Triassic and the Late Cretaceous. Ice ages occurred during the Ordovician and at the turn from Carboniferous to Permian.

Gas hydrates are far more important than coal, oil, and natural gas as carbon reservoirs. They occur in enormous quantities frozen into ice on the continental slopes of the oceans and in permafrost areas. Gas hydrates are formed by single-celled microorganisms known as archaea. Their main component is methane,

which can be extracted as a fossil fuel. During this extraction process the continental slopes are literally ploughed up, causing massive destruction of habitats. Current global warming could cause the methane to melt completely, thereby triggering a global climate catastrophe.

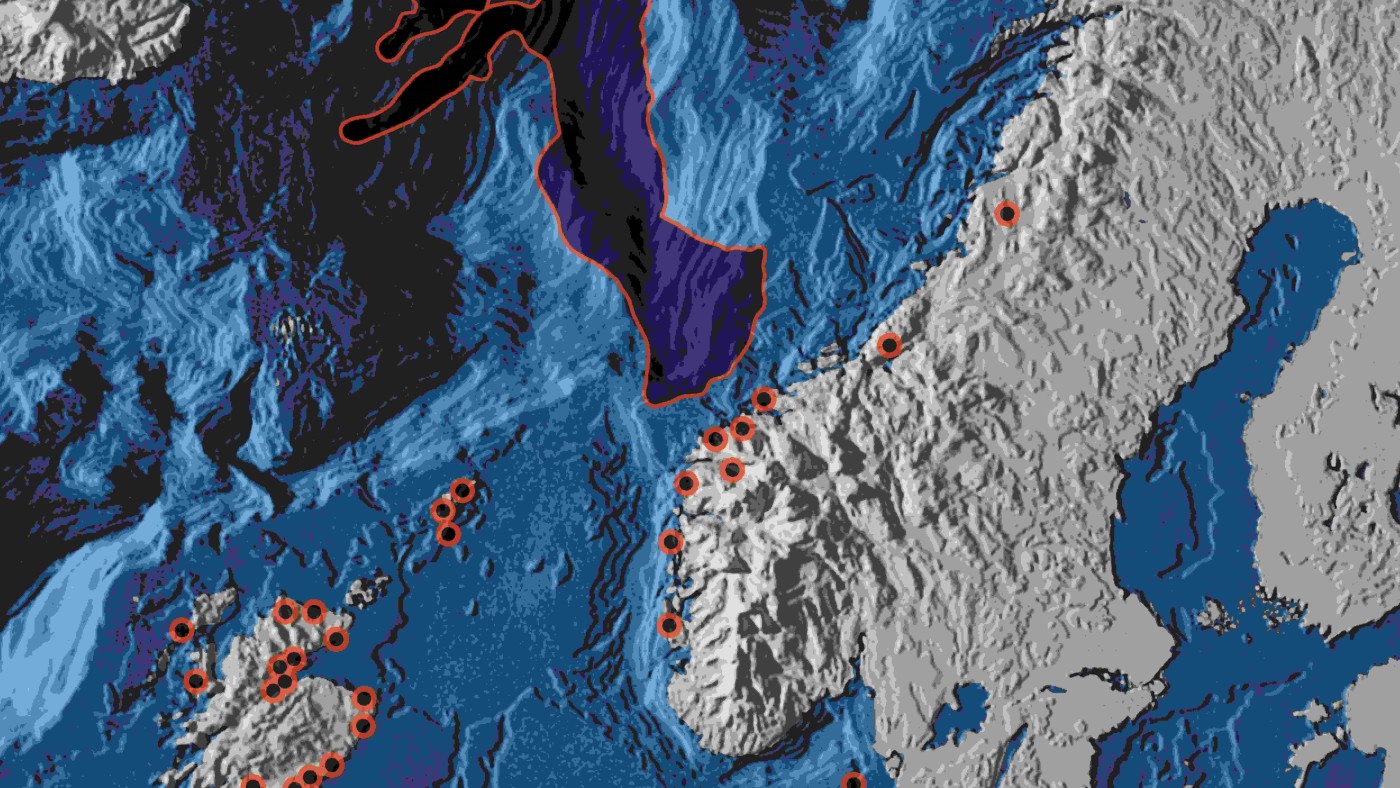

Manganese nodules are formed by iron bacteria on the ocean floor at a depth of over 4,000 meters. They cover a huge area in the Pacific – equivalent to half the size of Europe. Apart from manganese, the nodules contain high levels of nickel, cobalt, tellurium, and copper – important raw materials for computers, mobile phones, and car batteries. Manganese nodules grow just a few millimeters in a million years. Mining them using trawl nets destroys this deep-sea habitat forever.

It took about 200,000 years for the methane to be broken down and the climate to stabilize.

Approximately 8,200 years ago, the methane ice off the coasts of Norway began to melt. This resulted in a huge debris avalanche which cascaded into the water, creating a tidal wave up to 20 meters in height. If today’s gas hydrates were to melt, this would also trigger tsunamis.

Rocks as climate archives

Man as geological force

Steel, concrete, and plastic Since 2020, the amount of material created by humans has exceeded the total amount of biomass on Earth! Long after mankind has become extinct there will still be mighty deposits of steel, concrete, and plastic covering large parts of the planet. Traces of the Anthropocene can be found all the way down to the depths of the oceans in the form of heavy metals and microplastics. The warming of the atmosphere through greenhouse gases and the acidification of the oceans are also features of the Anthropocene.

The beginning of each geological epoch is defined by a global event, such as the first appearance of a living being. Which event should define the start of the Anthropocene is a subject of debate among researchers. The event should be one which is still detectable in sediments worldwide millions of years from now. The first appearance of Homo sapiens 300,000 years ago is therefore not a suitable starting point. One possibility would be the first atomic bomb test in 1945. The radioactive fallout that followed this and the further 2,100 or so explosions can be detected worldwide – and still will be in millions of years’ time.

Hall 6 is the oldest furnished room in the Natural History Museum. It is still known today as the “Kaisersaal” or “Emperor’s Hall”. There are two reasons for this nickname. Firstly, it originally housed the “Kaiserbild”, a painting of Emperor Francis I now on display by the staircase. Secondly, the hall’s decorative style is dominated by the building’s patron, Emperor Franz Joseph I.

- "Emperor Franz Josef Fjord, East Coast of Greenland” by Albert Zimmermann (1809–1888)

- "Emperor Franz Josef Land, The Abandoned Tegetthoff” by Julius von Payer (1841–1915)

- "Emperor Franz Josef Glacier New Zealand” by Adolph Obermüllner (1833–1898)

- "Franz Josefhöhe with the Pasterze Glacier” by Eduard Peithner von Lichtenfels

(1833–1913) - "Cap Tyrol, Emperor Franz Josef Land” by Julius von Payer (1841–1915)

- "Austria Sound”, a night scene of Emperor Franz Josef Land, by Julius von Payer (1841–1915)

The painting “Der Austria Sund” was lost and has been replaced by a modern work by the painter Franz Messner (2006). The painting “From Dalmatia” is the only image that does not make a reference to the emperor. It was produced by Lea von Littrow – the only female painter involved in the decoration of the museum. She worked under the pseudonym Leo Littrow.

As with all the corner halls on the mezzanine floor, Hall 6 also has a number of sculptures. These were created by Edmund Hofmann von Aspernburg (1847–1930).

Four pairs of figures represent the Four Elements which have been a constant since ancient times: earth, water, fire, and air. The other figures show several chemical elements (gold, silver, iron, copper, arsenic, lead, tin, and mercury) that were important as raw materials.