Hallstatt in the Early and High Middle Ages

There are no archaeological or historic sources proving that the Hallstatt salt deposits were used in any form whatsoever between the 5th and the 13th century. There are also no known finds in Hallstatt from the Early Middle Ages. However, place names, written documents and ground sources provide much information on life in the region around Hallstatt.General information on the Early and High Middle Ages

Early and High Middle Ages in Hallstatt

Place names

General written documents and ground sources

Establishment of monasteries

History of law and trade

Salt producers

General information on the Early and High Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages followed on from the upheaval of the Migration Period and were heavily influenced by the process of Christianization. Settlements and burial traditions changed during this time. Most people lived on farms or in small villages and hamlets. After numerous epidemics and regular crop failures, population numbers probably decreased compared with the Roman imperial period.Early and High Middle Ages in Hallstatt

We cannot assume that antique traditions survived in Hallstatt beyond the 5th century, and this may partly explain why we have not found any evidence in support of the exploitation of the salt deposit there in the Early or the beginning of the High Middle Ages. We may however assume that the location and existence of the salt deposit was still known. Although small-scale exploitation of saline water (natural brine) is probable, archaeological evidence of such activities is almost impossible, because the vessels used in the process would not have been different from other vessels used at the time. At the end of the 13th century, historiography brought into focus the area of the Hallstatt High Valley, and at this point archaeologists will have to give precedence to the miners.Place names

Looking more closely at the potential settlement areas down the Traun and south of the Salzkammergut, as well as at other lakes of the Salzkammergut, we will get a more nuanced picture of the time. Some evidence of Romanic peoples who remained linguistically discernible at least until their integration into the Bavarian Duchy, and who had not migrated might be found in the genuine ‘Walch’ (or ‘stranger’) name prefixes encountered in the region concerned, on the north lakeside and north of the Attersee Lake: Walchen, Seewalchen, Ehwalchen and possibly Einwalchen. The reason why these names have survived is probably the vicinity of these villages to Salzburg, the ancient Iuvavum, where circumstantial evidence suggests the existence of an important Romanic population in the Early Middle Ages. Slavic toponyms are found in the southern part of the Salzkammergut, roughly between the northern lakeside of Lake Hallstatt and Bad Ischl, and in field names in the environs of Bad Aussee.General written documents and ground sources

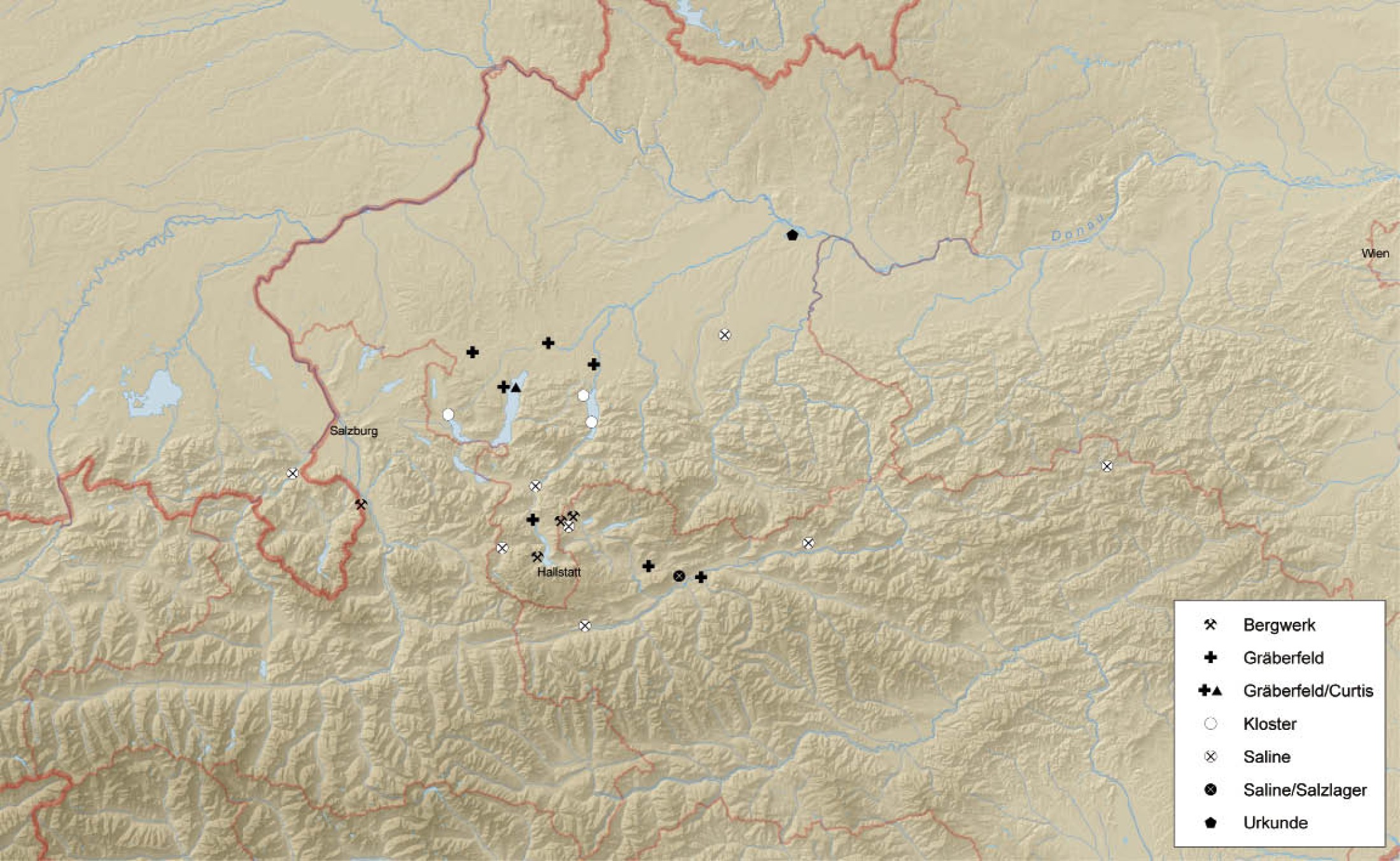

In Upper Austria, cemeteries are evidenced from the second half of the 6th century onwards. They are limited to the river valleys in the pre-Alps and either prove that the land was cultivated by Bavarian immigrants or that the local population adapted to the material and cultural values of the Merovingian period. So far, cemeteries further south have been evidenced by the old finds from Schöndorf (township of Vöcklabruck) and Frankenmarkt (district of Vöcklabruck), and the destroyed graves from the Kirchberg in Attersee. These may be connected with a duke’s court of the Agilofings family, from which developed the curtis Atarnhova (the royal court of Atterhof) mentioned in two documents of the second half of the 9th century. Wine growing is documented in Attersee by a source dated AD 790.The only closely datable cemetery of the inner Salzkammergut is the Bad Goisern site, dating from the end of the 8th century and, mainly, the 9th century, that is to say from the Carolingians: it is thus slightly younger than the known cemeteries of Krungl and Hohenberg in Styria. The latter are however situated beyond the region under study. Another cemetery difficult to date was discovered in Peiskam near Ohlsdorf. There is hardly any evidence of contemporaneous settlements; they are presumably coextensive with the present village, that is to say lying beneath today’s settlements.

Establishment of monasteries

In the eastern and southern border regions of the Bavarian Duchy, the foundation of religious houses was one of the most important factors in political and, in its basic sense, cultural development. All legendary topoi or reasons for specific foundations aside, several actual factors may have featured in the selection of the locations: good road connections, natural resources, or the potential for future settlement. Antagonistic criteria may also be conceivable, such as solitude, deliberate retreat into forested regions, contemplation. We will have to rely on interdisciplinary research to find answers to these questions.We do not know where the original parent convent of the Mondsee Monastery, founded by the Bavarian Duke Odilo, come from, in AD 748, but it may have been Monte Cassino, Salzburg or Regensburg. After Tassilo III of Bavaria had been deposed, Mondsee became an imperial abbey in AD 788 and passed to the bishop of Regensburg prior to AD 837. In the Middle Ages, Mondsee rated among the most prominent scriptoriums of the time, and the famous Tassilo Chalice may have been produced in Mondsee. The first abbey on the Traunsee Lake, the abbacia trunseo, is supposed to have been founded in Altmünster about AD 909. The abbey presumably perished in the Hungarian invasions of the 10th century. The women’s convent at Traunkirchen was founded in the first half of the 11th century by the Counts of Raschenberg- Reichenhall, who were later to become the owners of the Hallstatt parish.

History of law and trade

In 1312, the monastic rights covering Hallstatt reverted to Queen Elisabeth, including rights of way, forestry rights, brineboiling rights and the right to hold assizes. Whether these rights had previously been exercised by the Traunkirchen nunnery in relation to Hallstatt is unknown. With respect to the history of law and trade, the Raffelstett customs regulations are an excellent source dating approximately from 905 A.D. This record not only mentions customs duties applied in East Bavaria, but also traded goods, among which salt is most important. Distinctions are made between salt for personal use and salt as an article of trade.Next in importance to salt are wax, slaves and horses. The document mentions ships from western regions that have to pay their customs duties in Linz in salt. The salt probably came from the saltworks in Reichenhall, Bavaria. ‘Naves, que de Trungove sunt’ are more closely connected with the region under study. Since they are mentioned in connection with salt carts using the legal trade route through the Enns ford, we may assume that they transported salt. The geographic concept of Traungau is not clearly defined, but the eastern border presumably went along the river Enns. The customs authorities do not mention where exactly the Traungau ships came from.

Salt producers

Scholars assume that the salt came from the saltworks mentioned in the deed of foundation of the Kremsmünster monastery dating from AD 777. The saltworks are supposed to have been situated in what is today Pfarrkirchen, in the municipality of Bad Hall. Further brine springs are mentioned in connection with the king’s court in Villach, AD 979, and on the occasion of its foundation in 1074, the Admont Abbey was given a brine spring, documented as early as 931. We know of four Styrian salt mines worked prior to the high-medieval mining, namely the saltworks of Halltal near Mariazell (mentioned in 1025), Grauscharn near Pürgg (1182), Weißenbach near St. Gallen (1152?) and Ahorn, Altaussee (1147).The mining of the area of Michelhall on the west side of the Sandling prior to the High Middle Ages may be assumed, while two further names (Aigen, Berg Gülch) cannot be precisely located. The years only refer to entries in documents; the use of the springs may date back much farther. The salt producing process in saltworks of the Early Middle Ages can be reconstructed on the basis of the documents available for Reichenhall. The production unit is the pan, the patella. The brine is first lifted from the putiatorium (well) into the patella (the pan) by means of a boom – a device used for raising water from wells out on the Hungarian puszta. In the pans, the brine is refined to c. 20% salt content and boiled in fornaces (furnaces). The names mentioned in the Reichenhall documents suggest that a large part of the population lived according to Romanic traditions. Salt mining at the Untersberg may be connected with this segment of the population.

(Ruß, D. – Reschreiter, H. - Loew, C.)