Results of animal bone analyses from the Salzbergtal valley

In the course of the excavations in 1993-94, a thick layer of animal bone was discovered. The dense accumulation of bones baffled the archaeologists, who handed them over to the archaeozoological department of the Natural History Museum, Vienna, for analysis. The bones are connected to salt mining in the region and to the pits in the ground discovered in the 19th century that would have been used to cure the meat. These layers of bones were all found near such pits. Analyses have revealed a well-organized and highly specialized meat curing industry on a large scale.Identified animal species and skeleton parts

Composition of the pig bones

Interpretation of the missing skeleton parts

Sex determination using pig jaws

Age of pigs at slaughter

Signs of dismemberment

Thoughts on transport

Age and sex of the other animal species

Identified animal species and skeleton parts

This revealed that they are mainly pig bones, but represent only specific parts of the skeleton. More than 10,000 bones were

identified: 60.5% of them were pig, 21.5% sheep and goat, 17.6% cattle, and only a few attributable to other species. The

marked prevalence of pig bones on the Hallstatt site contrasts strongly with the majority of prehistoric settlement waste

in Central Europe, which shows a predominance of cattle bones. But even more remarkable were the largely undamaged condition

of many of the bones, and the marked imbalance of the various parts of the skeleton. About half of the pig shanks, and of

the shin bones of the small domestic ruminants and the cattle had been preserved unbroken, that is, not cut by butchery.Composition of the pig bones

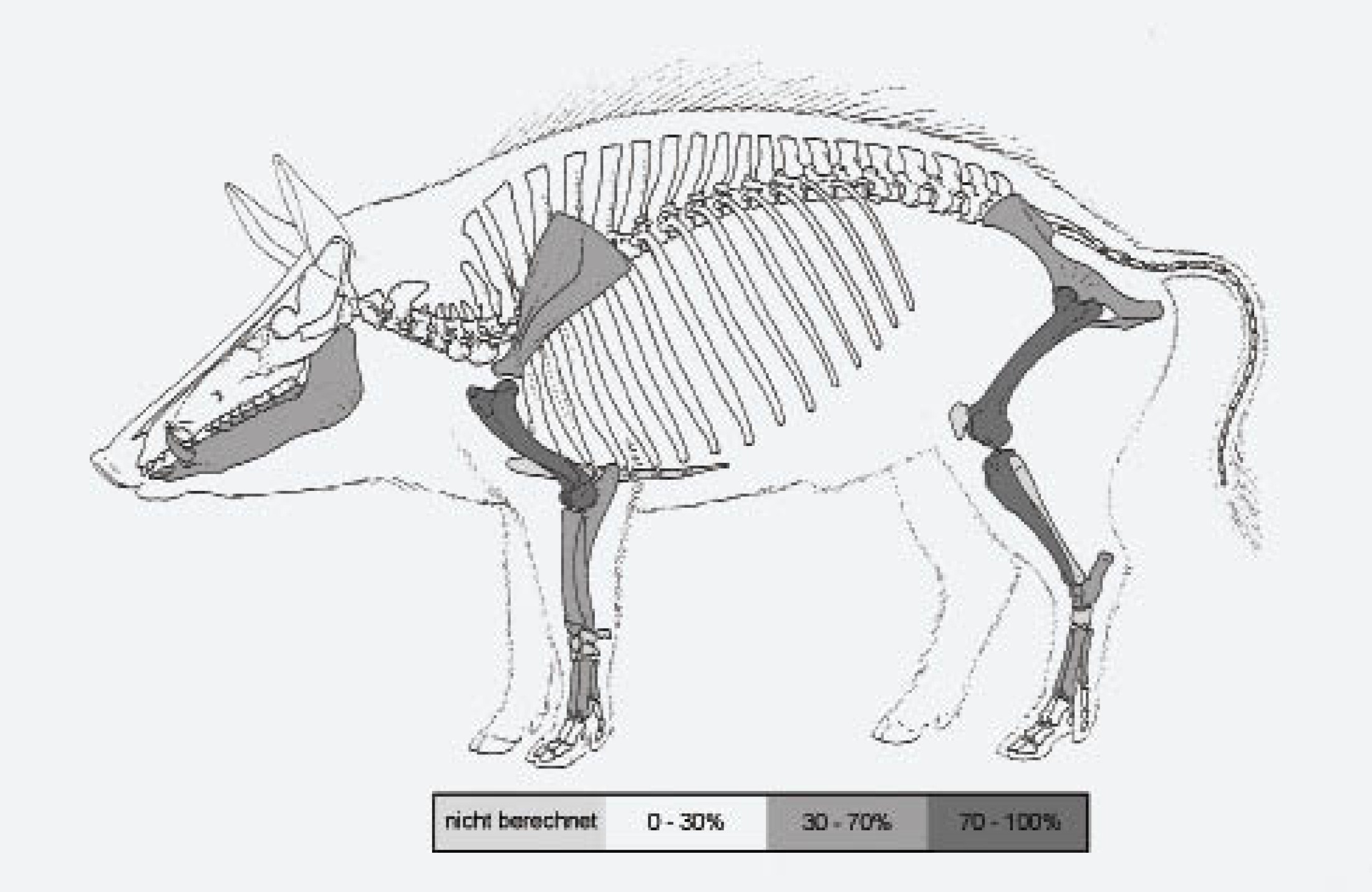

Among the pig remains, there were practically no cranial bones, no vertebrae and no ribs, while there were masses of long, meat-bearing bones and also (rather worthless) lower jaws. With the sheep and goats, there were again plenty of lower-limb, metacarpal and metatarsal bones, also long bones, but again almost no crania or bones from the proximal postcranial skeleton (vertebrae, ribs, etc.). The finds were much the same for the cattle, but the long bones, except for the metacarpal and metatarsal bones, were quite frequently split or broken.Interpretation of the missing skeleton parts

Such unequal distribution of the various parts of the skeleton is virtually unparalleled in prehistoric settlement waste. Normally, the various parts of the body are found in roughly the same proportions, because the animals were mostly slaughtered and eaten in one place. The absence of certain parts of the skeleton can only be explained if some parts were removed from the site, or if those parts found on site were specifically brought there from the place of slaughter. Considering the unfavourable location of the narrow High Valley, and the fact that ist inhabitants specialised in salt mining, the latter hypothesis seems more probable.Sex determination using pig jaws

Further investigations focused on the pigs, whose jaws in particular provided useful clues. Since the canines formed differently in sows and boars, it was possible to determine the relative proportion of the biological sexes. There were 102 male jaws to a mere 9 female jaws, an extreme imbalance compared with what is found on Bronze Age rural settlements. There female animals prevail, while in the larger Early Bronze Age trade centres, supplied by hinterlands, we find a more or less pronounced predomination of males – presumably gelded for better tasting meat.Age of pigs at slaughter

The age at slaughter could be estimated by assessing changes in tooth eruption and attrition. The average slaughter age of the pigs was 1½ to 2 years, with practically no evidence of either younger or older pigs. This was clearly the best slaughter age for the highest quality meat. In primitive domestic pigs, the slaughter period would have been winter. The fact that there are no piglets or fuller mature pigs is a sure sign that the animals were not bred and slaughtered at the site, but brought into the High Valley as carcasses.Signs of dismemberment

Despite the absence of potentially revealing skeletal elements, the few sporadic finds of cervical vertebrae do show traces of chopping, while the jaws display systematic traces of cuts at the upper end, at the point where the skull must have been removed from the torso. Other cut marks were less systematic. Although there is no further information on the method by which the pigs were cut up, the lack of such traces on the long bones indicates that they were left uncut for the meat to be processed further on the bone. Since, however, most of the torso bones were missing, the torso was presumably removed along with the entrails. What was left was a carcass, without the cranium but with the lower jaw, its big canines protruding like hooks, and this was somehow attached to the four lower limbs, with the spine and ribs previously removed.Thoughts on transport

Was this the way the carcass was suspended and conveyed uphill? From the snout to the base of the tail, a Hallstatt pig was about 110 cm long. Assuming a live weight of 85 kg for the pigs, which were then still very much like wild boars, the carcass including the bones would have weighed approximately 50 kg – a bearable load if suspended for instance on a stave and carried on shoulders.Age and sex of the other animal species

The osteological findings from the other species support this. They too show a predominance of gelded animals in their prime, while there are neither very young nor very old animals. The uneven distribution of the various parts of the skeleton again suggests the delivery of selected pre-processed parts that were traded in. All this of course presupposes productive stock breeding farms in the surrounding valleys and elaborate logistics. And of this there can be little doubt when we consider the wealth of quite amazing finds.(Pucher, E.)