Becoming (Hu)man

The new permanent anthropology exhibition deals with the general theme of hominid evolution and looks at the evolution of man through to the Neolithic period.

Bipedalism and brain evolution are the two main themes addressed in Halls 14 and 15. Starting with our closest living relatives the trail leads through several palaeoanthropological thematic modules to the emergence of Homo sapiens, i.e., cosmopolitan modern man adapted to a variety of natural habitats.

Visitors to the Museum have the opportunity not only to see the evolution of man as a historical, biological process, but also to perceive cultural development as a significant component of humanization. A modular approach to the knowledge content was chosen for the exhibition, enabling both a playful, interactive access and the option of an in-depth look at more complex issues.

A Hands-on Experience

A total of six hands-on stations have been created to make the different stages of humanization literally “palpable” to visitors, particularly those who are sight-impaired or blind.

One of the highlights is the CSI table. Inspired by the plot formula of the TV series, the CSI table gives visitors the opportunity to determine the age, gender, and cause of death of a virtual skeleton using a microscope, magnifying glass, and isotope investigation.

Visitors can also take photographs of themselves as prehistoric men or women and send the images by e-mail. This Morphing Station is a joint venture with the Smithsonian Natural History Museum in Washington, DC (http://humanorigins.si.edu/).

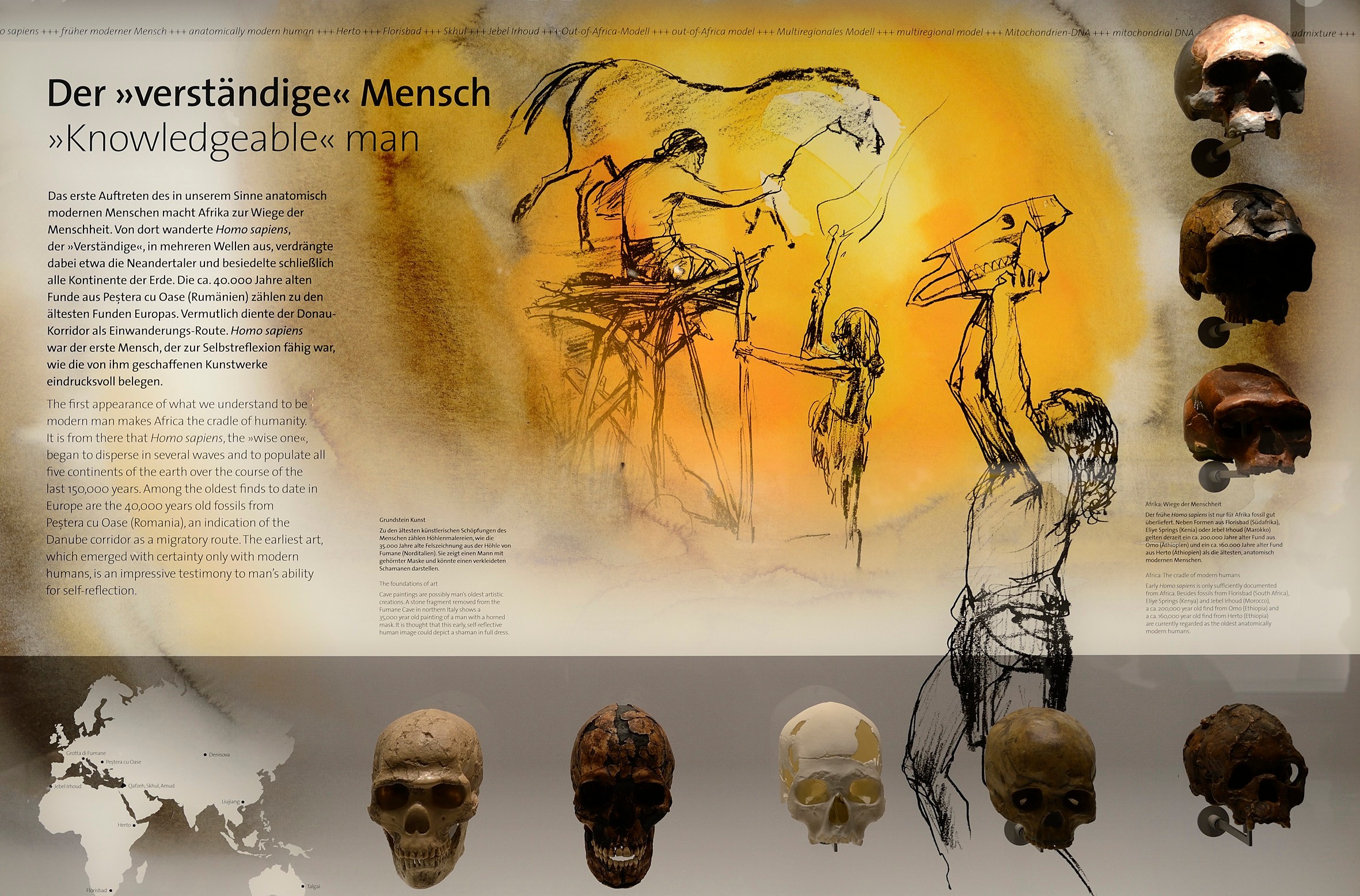

Other stations allow visitors to detect the difference between the skull of a Neanderthal and that of a Homo sapiens by touching the skulls. Also, the footprints left behind in volcanic ash by three already bipedal hominids some 3.6 million years ago in what is now Tanzania have been recreated in the floor of the Museum of Natural History.

The Laetoli footprints, as they are known, were discovered in 1978 and provide the oldest evidence of bipedal (i.e., upright)

locomotion. The western track was made by a single individual; the eastern track by two individuals walking one after the

other in the same footmark.

At the NHM these footprints lead directly to the life-size reconstructions of Lucy and a male member of the same species, Australopithecus afarensis. The Augmented Reality Station vividly replicates the transitional stage from quadrupedalism (i.e., four-legged) to bipedalism (two-legged).

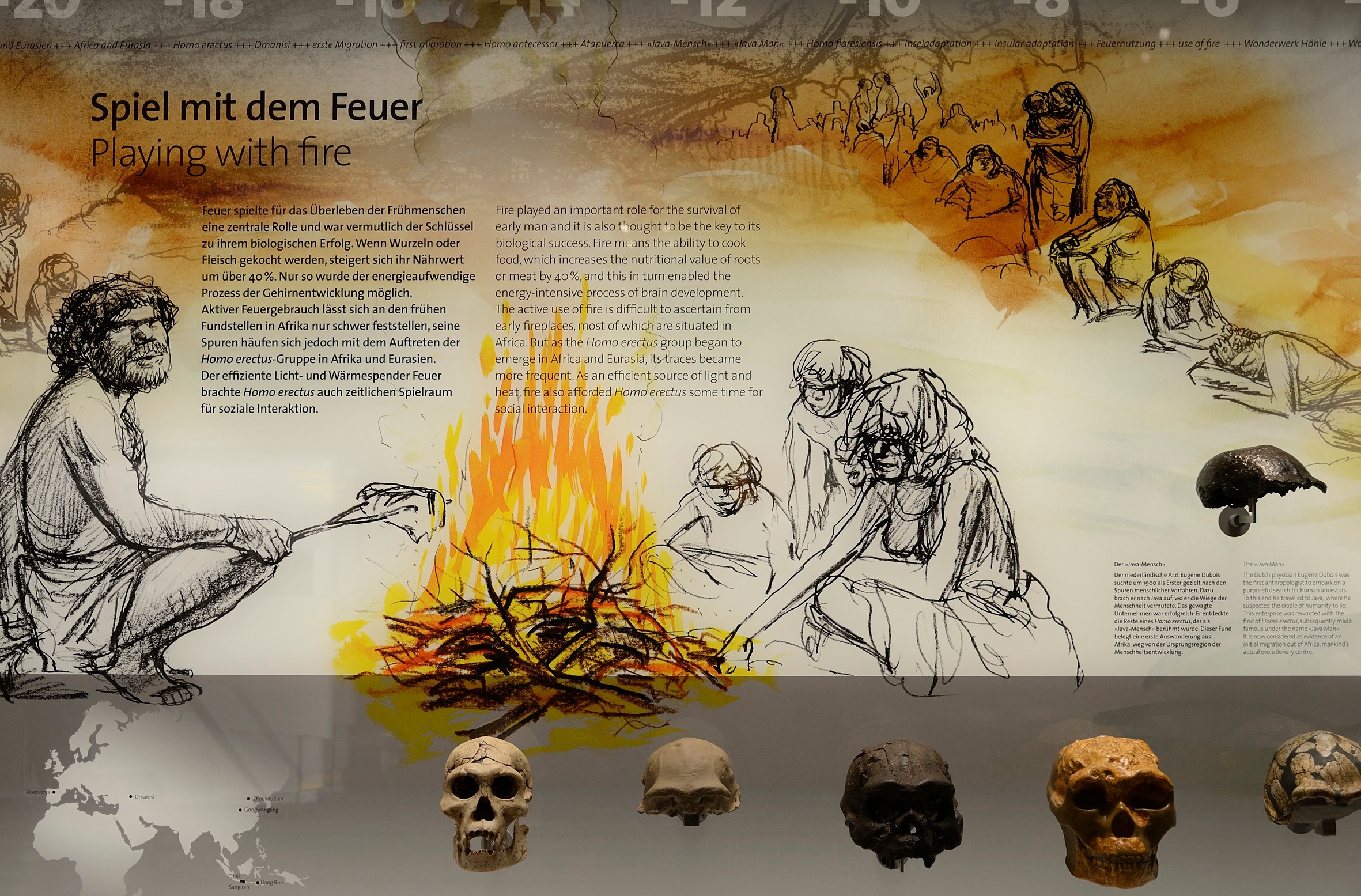

Another hands-on station comprises the sensational find of the Wachtberg twins near Krems, a 27,000-year-old double burial site of two newborn babies discovered in 2005. An opening in the floor containing the flickering simulation of a prehistoric hearth complete with fire is certain to be a particularly vivid experience, especially for children.

Bipedalism and Brain Evolution - Two Key Themes

Of the exhibits acquired for the exhibition, particular mention should be made of the mouldings of Australopithecus sediba, a new species discovered in South Africa. It is currently under discussion as a potential direct ancestor of the genus Homo. The insights gained as a result are to be experienced and debated at the Museum.

One of the most interesting new finds of the last few years is without a doubt that of Sahelanthropus, potentially - and controversially - the first bipedal hominid, found in Chad and dated to around 6 million years ago, and also diminutive man (or “Hobbit”, approx. 17,000 years old), which is still the subject of much debate among palaeoanthropologists. Other focal points include the Denisova hominin, a previously unknown human form discovered in the Altai Mountains of Siberia, and the surprising findings of palaeo-genetic investigations.

The exhibition also places particular emphasis on “type specimens” and the latest fossil finds, many of them controversial, alongside those finds of pre-humans and early humans that have been known to science for a long time. The Who’s Who includes finds of the earliest bipedal hominids dated at approx. 6 million years old and therefore the oldest ancestors of man - Sahelanthropus tchadensis and Orrorin tugenensis - as well as contemporaries of anatomically modern man discovered only a few years ago, the Denisova hominins and the diminutive Homo floresiensis discovered on the island of Flores.

Homo floresiensis remains puzzling to the experts as its extremely small body and skull make it so radically different from anatomically modern man. Unsurprisingly, interpretations remain highly controversial, ranging from an insular adaptation of Homo erectus to a pathological variation or simply a long surviving discrete species of non-modern human.

The installation featuring a glass “genealogical shrub” (rather than a linear phylogenetic tree) is designed not only to underscore just how non-linear man’s evolutionary process has been, but also to highlight just how vague our attempts at reconstruction based on fragmentary fossil finds actually are.

Other important elements of the knowledge conveyed here include the elaborate and very realistic soft tissue reconstructions of Lucy or Homo neanderthalensis, made by French artist Elisabeth Daynès, and the impressively designed reconstruction of a Proconsul (an extinct genus of primates classified as one of the earliest representatives of human-like beings) by Iris Rubin, a staff member of the Taxidermy Department at the NHM.

The decision to introduce multiple layers of textual content reflects the attempt to appeal to the different interests of visitors to the Museum, and also the need for a more in-depth exploration of the knowledge content. The exhibition offers lots of opportunities to discuss questions of taxonomic classification and to explore the process of humanisation through illustrative examples, supported by media technology; also, to address and pinpoint the outstanding and unanswered questions of this complex process, which can only be resolved through an interdisciplinary approach.

The evolution of man should be seen not just as a historical, biological process, but also as the result of cultural development as a key influencing factor, and both these aspects played a huge part in formulating the concept for the contents of the new permanent exhibition.